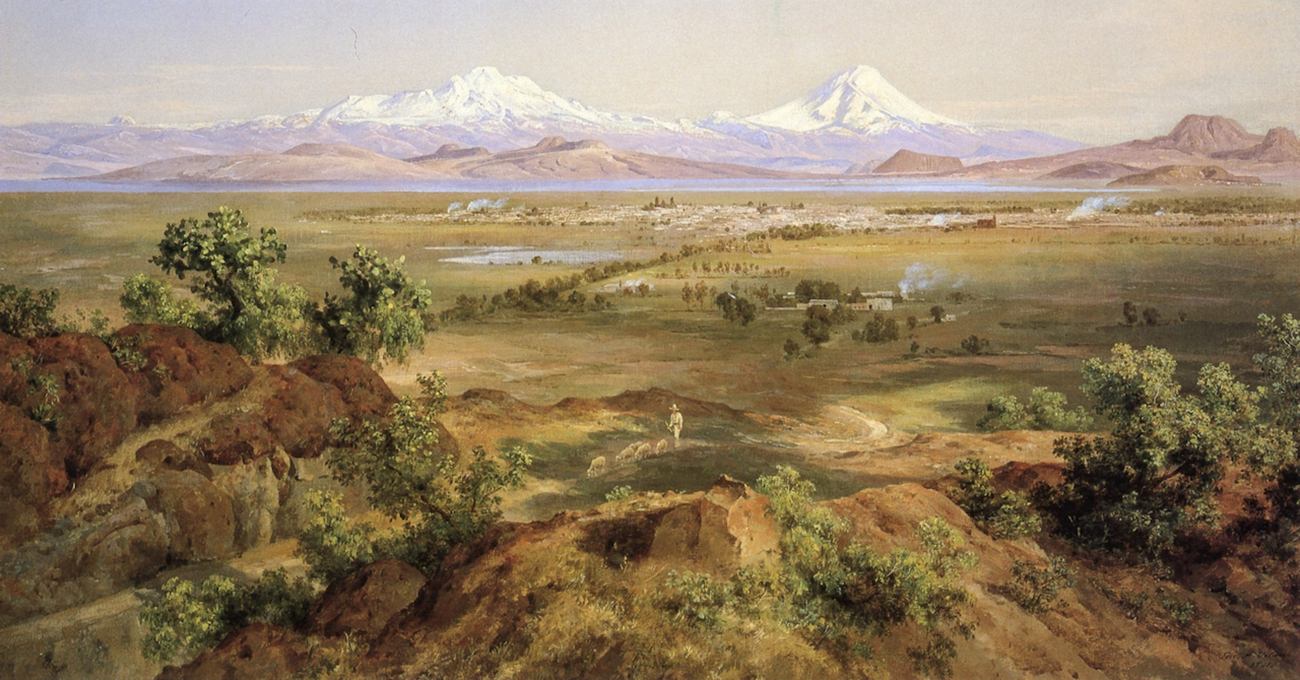

The Mexican artist José María Velasco is an outstanding example of integrating art and nature, sensibility and observation, motion and stillness. In his landscapes, we appreciate the transition of two different epochs—the cornfields of the estate suddenly tripping over the dense locomotives’ steam. The National Gallery in London is set to unveil an exhibition on March 29th that reframes Velasco’s legacy—not just as a painter of Mexican landscapes, but as a visionary 19th-century artist whose work speaks to the world. This marks the first major international presentation of Velasco’s art since 1976. In a conversation with one of the curators of the exhibition, artist Dexter Dalwood, Claudia Madrazo explored his perspectives.

Reinventing Landscape Painting

I see Velasco—Dexter starts—as similar to contemporary research-based artists. He was interested in many interdisciplinary activities—being a naturalist fascinated by geology, zoology, and enthusiastic about new science entering Mexico in the mid-1850s. This was when revelations about the planet being 350 billion years old emerged. Velasco incorporated these ideas into his work.

His paintings serve as receptacles not only for the landscape's topography but also for what lies beneath. He wanted viewers to consider the history of each location in terms of human history—thinking about the past, present, and suggesting future changes. This intentioned vision distinguishes him from contemporaries who came to Mexico and painted landscapes. He focused on what he wanted viewers to think about and experience.

The exhibition aims to present Velasco as an artist first and foremost—a painter who lived between 1840 and 1912, almost the same dates as Cézanne, but working in Mexico. With this exhibition, we want to emphasize that rather than the historical idea of him representing nationhood or Mexico's international image during the Porfirio Díaz era.

His work is diverse—there's a surrealist aspect to pieces in the Geological Museum in Santa Maria, numerous botanical works, and an enormous number of drawings that could be shown in different lights. This exhibition focuses on images from the Valley of Mexico—30 works total: 25 paintings and five drawings.

Dalwood explains that his essay in the catalog is titled "Landscape as the Site of Change" because, unlike European painters of the same period, Velasco documented the extraordinary changes happening during industrialization. He captured railways and factories coming in, the changing landscape, and what remained of Texcoco's Lake. His paintings suggest the difference between what the landscape was like when the Spanish arrived, what it was when the Mexica arrived in the valley, and what it had been a thousand years before that.

Velasco reinvented landscape painting. His work is realistic in that the botanical plants in the foregrounds of the 1875-1877 Valley of Mexico paintings are so detailed that they could be used to identify those plants. By constructing the physical space, he makes enormous changes to the viewer's perception. “The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel” (1877) view is reconstructed—it does not exist exactly like that. He brought in an outcrop of rock as a compositional device, dropped the perspective below the horizon line to bring everything forward, and painted the city with identifiable detail that would not be visible from that distance. It looks compelling but is a constructed mind map designed to make you think about specific things.

José María Velasco Gómez (1884)

Velasco on the Shoulders of Giants

I cannot imagine—Dalwood continues—Velasco had not read Humboldt's books, which were translated into 70 languages and were tremendously important. Humboldt's concept of an "overview of nature" was revolutionary—separating science while considering how everything interconnects in a pre-Darwinian way. His theories imagined connections between geological features like tectonic plates and volcanic valleys. Humboldt brought an incredible overview to these ideas and essentially invented the concept of nature as a subject in its own right, leading to fields like ecology. Given Velasco's engagement with scientific papers and societies, Humboldt's thinking, and through him Goethe's ideas,influenced his practice.

Velasco brings this empirical scientific approach, but it is not cold. Like Humboldt, he is trying to understand what connects all these things. During his lifetime, painting styles changed enormously—mannerism, symbolism at the end of the 19th century, and impressionism. These movements did not affect him because his project and interests were quite clear.

His teacher, Eugenio Landesio, made an enormous difference. If Landesio had not come to San Carlos Academy to teach landscape painting, perhaps Velasco would not have found his path so quickly. Landesio quickly recognized Velasco's talent, which eventually overshadowed his own. Velasco mastered technical drawing as well as perspective rules and then unlearned some conventions to find his own particular style.

While Landesio's paintings retain the warm light of Rome or Italy with soft romanticism, there is no soft romanticism in Velasco. His work is hard but not cold, with underlying strength in its particular depiction. He worked out how to paint the light in this valley and capture the extraordinary cloud formations unique to this region. His paintings are not just impressions—he is creating something deliberate.

Towards the end of his life, Velasco’s work becomes mystical. The large comet painting in the exhibition is extraordinary and different from his earlier work. It is like a meditation on time itself. The comet he depicts is one he saw in 1882, but he painted it in 1910 when Halley's Comet appeared. This represents universal time rather than human time—comets like Halley's return every 75 years. It is especially poignant as he was nearing the end of his life. Dalwood believes that this painting will be a surprise for the exhibition visitors.

José María Velasco Gómez (1910)

Exhibition Impact

This exhibition offers an opportunity to introduce a Mexican master largely unknown outside his home country to European audiences. By highlighting the connections between Velasco and his European contemporaries, the show contextualizes his work within global art movements while emphasizing his distinctive scientific approach to landscape.

The exhibition establishes important historical connections, including Velasco's influence on Diego Rivera, and encourages viewers to consider parallel artistic developments in Europe and Mexico during the late 19th century. Through this international presentation, Velasco's legacy as both a skillful landscape painter and interdisciplinary thinker can finally introduce him into the canon and receive the global recognition he deserves.

Transformación, Arte y Educación is proud to have collaborated with the Family and Children Program of the National Gallery in designing the free workshops that the museum will offer.