A stroke is a self-affirming act: I am here. The gesture has more to do with the sender than with the receiver: the line exists because a hand traces it, and the eyes that look at it will come later. Even more, a line can become an extension of oneself, the meeting point between experience and expression, the testimony that combines reality and desire. From there emanates the transformative power of art, from its ability to recognize the inner world and take it to the outside, not only on the aesthetic level but also within its historical and social context. The line is an extension—a testimony—of our movements and trajectories.

At the same time, the stroke can become an invaluable travel companion. Self-knowledge is a path that, at times, can be confusing and rocky. Keeping records of our processes helps us preserve them for future reference and allows us to be our own witnesses. These works that arise spontaneously in the margins of notebooks and in the corners of napkins (actually, on any surface that lends itself to it) are more than a mirror. Despite not specifically coming from the search for transcendence, they have the gift of permanence. People change, but their drawings and writings serve to crystallize over time a fragment of what they once were.

Thus, the line has immense symbolic power since it can leave a record of an event, a time, and a place. Above all, it recognizes the complexity and relevance of a person's identity in certain circumstances. Simply put, some lines say here I am, now, like this, and it matters. There are times when that statement can make all the difference.

Óscar Murillo and its affective bond with art

Óscar Murillo was born in Valle del Cauca, Colombia, in 1986. At 11, he emigrated with his parents to south London. Amid this geographical and cultural change—whose assimilation was even more difficult as he spoke little English and did not know anyone in his new city—Murillo took refuge in drawing and discovered the power of art as a mirror, voice, and map., but above all, it is a safe place to explore your identity. These first strokes laid out the path he would follow in the following decades.

However, his route was always strongly influenced by his roots and context. While he was advancing in his studies for a degree in Fine Arts at the University of Westminster and even his master's degree at the Royal College of Art, he worked in the early mornings as cleaning staff, as his father did when he arrived in England. Thus, his works address topics such as migration, community, and global social and economic dynamics.

On the other hand, his interest in the affective qualities of materials led him to experiment with different formats, dimensions and spaces, trying to place his work in living environments (such as schools or churches) to question the barriers between the working class and the world of work—art by recreating factories and popular festivals within museums and galleries. For him, the greatest virtue of art is its ability to bring together and connect people, to be a vehicle to establish and strengthen links that touch but are not limited to the conceptual level but rather overflow into the field of practice.

In general, Óscar Murillo is skeptical about artificial limitations. For him, art is almost a living being, organic matter that must respond to its own needs and processes and those of its audience, not only to the conventions of the artistic market. Regarding this, he comments: "I reject the framework. Each work delimits its own space, which seems born of chance or is waiting to be reinterpreted as time passes."

In 2019, Óscar Murillo was nominated to the Turner Award, one of the most prestigious awards in the world of art. Despite not knowing each other previously, the four nominated artists soon realized that similar interests and problems crossed their works, so they decided to come together and receive the award as a collective, as a way to emphasize their message of community and solidarity. Since then, the attention of the art market and critics has been placed on Murillo, whose work has been revalued both academically and economically. The artist recognizes this phenomenon and describes his work as a “social trigger” that helps insert his criticism into the very spaces he questions.

Frequencies: resonances between youths

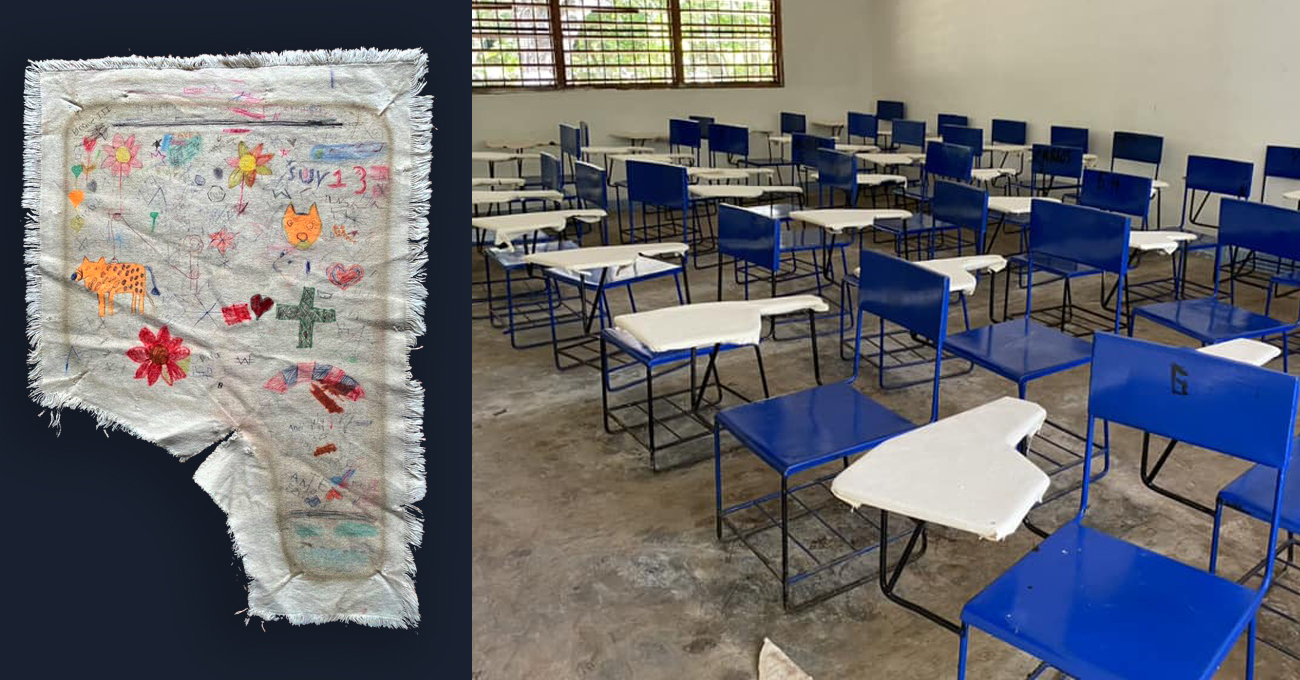

In 2013, Óscar Murillo visited La Paila, his hometown in Valle del Cauca, where, for the first time, he asked permission to cover the school desks with blank canvases. A few months later, the students not only got used to the presence of the fabric on the desk but also fulfilled the artist's mission: they felt confident in writing, drawing, and scribbling on it. This is how the Frecuencias project began, an initiative that, for almost 10 years, has partnered with various educational institutions and local authorities to bring and install blank canvases to schools around the world.

Clara Dublanc, co-director of the Frecuencias Institute, clarified that this collaborative work must move away from paternalistic and condescending views since these drawings are testimony to the complexity of the experiences of young people around the world. Murillo himself has explained that "the idea is to let these children explore the intimate reality of the school desk, to make marks of their desires," and he adds that he sees the canvases as "recording devices" that record the students' thoughts. Once the canvases are collected, they are sent back to the studio, where the artist emphasizes the unifying power of the project by sometimes sewing fabrics together, thus intertwining the perspectives of children from totally different latitudes and contexts.

The archive, made up of thousands of canvases edited by more than 100,000 students between 10 and 16 years old, continues to grow and has been exhibited in emblematic spaces of the artistic circuit, such as the Venice Biennale (Italy), the Triennial Aichi (Japan), the Hangzhou Triennial of Fiber Art (China), to name just a few. For Murillo, the next step should focus on digitizing these pieces, making a database accessible to everyone, inspiring more young people to explore their creativity and expressiveness, and realizing the links they share with their contemporaries throughout the planet.

In 2022, the Frequencies Institute — with the support of Fundación TAE, gallery kurimanzutto and regional allies such as Baktún Pueblo Maya, Fundación Haciendas del Mundo Maya and the Coordination of Telebachilleratos of Yucatan — collaborated with schools in the communities of Tekantó, Izamal, Muxupip, Xcanchakán, Sisal, Benito Juárez, Tepakán, Valladolid, Tahmek, Tekal de Venegas, Timucuy, Ekmul, Mayapán, Hunuku, Yaxkukul, Free Unión, Texán de Palomeque, Subincancab, Tekom, Yokdzonot presented, Xocempich, Euán, Tiholop, Ekmul and Hunuku, as well as in Cancabchén and Conhuás (Campeche). Almost 2,000 students and just over 80 teachers were reached. In this way, the perspectives of the Mayan youth of the Yucatecan Peninsula were also integrated into this collective and multicultural archive that invites us to reconsider how we look at, create and share art.